TESTIMONY

“Jewish Panorama” 2 (80), February 2021

Review by O. Balla-Gertman of the novel “Testimony”

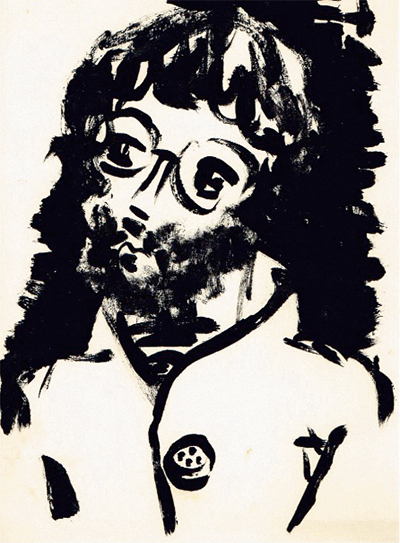

Portrait of the author. Artist Olga Ogneva

We would see the genetic kinship of the Israeli prose writer’s novel with Kafka’s texts even if the author had not provided the book with an epigraph taken from him. The kinship is not very close, like between uncle and nephew, grandfather and grandson: the resemblance is undeniable, but there is much else besides. Vidgop is more concrete, more psychological, more sensual than his “relative” who tends toward formulaic expression (among his ancestors is Bruno Schulz with his sensual exuberance). In any case, we have before us the fruit of the same branch of European literature that produced the dreamers of Prague and Drohobych.

Literature knows how to be European even when written in Israel, and in Russian at that: it’s a matter of worldview models. The time of this text is an indefinite European everytime (under Franz Joseph? under Queen Victoria?), the place is something like Europe in general: what is narrated, it seems, could have happened anywhere and anytime. The text, deliberately correct in its literariness, seems translated. And it is indeed a translation: from pan-European into the author’s native, transparently precise Russian.

“My family, having long since gone bankrupt, managed to make itself a cozy little nest near Trieste. And there my numerous virgin and widowed sisters from morning till night ground down the bones of my dear mother, father, and unfortunate brother…”

What for Kafka and Schulz is living contemporaneity, for the author is a subject of careful, deliberate reconstruction.

There is almost nothing Jewish as such here—in the narrow ethnographic sense. Those few places where it appears (well, for instance: “The life of a righteous Jew consists in observing six hundred and thirteen commandments. The restrictions we impose on ourselves seem like salvation to us. We cover ourselves with them like a shield to forget the truth that drills our brain relentlessly”) change nothing in this regard. But precisely for this reason the novel seems to me very Jewish—and related to Kafka in just such a deep sense: in the universality of a view that reveals fundamental structures.